-

What sex were you assigned at birth?

1 = male, 2 = female, 3 = intersex, 4 = other, namely,

5 = prefer not to answer

-

What is your gender identity?

1 = man, 2 = women, 3 = non-binary, 4 = gender queer,

5 = other, namely, 6 = prefer not to answer

However, important cultural distinctions are present in the understanding, definitions, and language surrounding sex and gender. Many countries around the world do not recognize that sex at birth and gender identity may not align; they conceive of sex and gender as necessarily binary (i.e., male or female). Additionally, in several languages, the distinction between sex and gender does not exist and the same word is often used to refer to both. In these cultural contexts, integrating sex and gender in traumatic stress research may come with additional challenges (Langevin, et al., 2024). The Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress is the ideal context for reflecting on these complex issues and for bringing the field forward through innovative approaches while respecting cultural differences.

Projects

Research on traumatic stress has highlighted notable sex and gender differences across various aspects of trauma, including the types of events experienced and responses to treatment. For example, men are more frequently exposed to war-related traumas, injuries, or physical assaults. Conversely, women are more prone to experiencing childhood maltreatment, sexual assault, rape, or intimate partner violence. Additionally, women are more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and tend to do so earlier in life. Emerging evidence suggests that men and women may respond differently to treatments. Finally, transgender and gender-diverse individuals report higher rates of lifetime traumatic experiences and current PTSD compared to their cisgender counterparts. To better understand how sex and gender interplay with various aspects of the experience of trauma and traumatic stress, more methodologically robust studies are needed. Unfortunately, there are many roadblocks to the integration of sex and gender considerations, especially in cross-cultural traumatic-stress research involving non-western and low-to-middle-income countries (LMIC).

Through the implementation of this Sex and Gender Priority Area at the Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress (GCTS), we aim to help bring the field further through various research projects and the development of methodological tools that will be elaborated collaboratively by the diverse members of our group. As first steps, we may:

-

Identify ongoing GCTS projects integrating sex and gender considerations and inventory the strategies they used to do so.

-

Survey members of the GCTS on challenges they faced when trying to tackle sex and gender in their projects and on effective and less effective solutions they implemented or considered to overcome these challenges.

-

Based on points 1 and 2, prepare a toolbox with concrete recommendations for effective and culturally sensitive integration of sex and gender in cross-cultural traumatic stress studies.

Do not hesitate to contact Rachel Langevin. Collaborators are welcome (CAW). if you wish to get involved or to share project ideas that you have for this priority area.

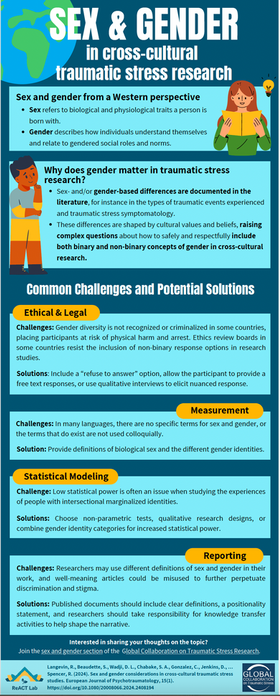

INFOGRAPHIC

How can we improve our approach to gender diversity in international traumatic stress studies?

Our new infographic explores key challenges—legal, ethical, measurement, statistical modeling, and reporting—and offers practical solutions.

Please download the infographic in:

French

Sex and Gender Orientation

Topic leader: Rachel Langevin, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

Within the GCTS we aim to explicitly consider sex and gender aspects across all projects.

n many western and high-income countries, an emphasis is placed on distinguishing between sex and gender in psychological research to better understand their distinct influence on study outcomes (see figure below for definitions). In these contexts, this simple and straightforward approach to measuring sex and gender in survey-based research is recommended to encourage reporting of comparable data across studies (Langeland & Olff, 2024):

References

Langeland, W., & Olff, M. (2024). Sex and gender in psychotrauma research. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2024.2358702

Langevin, R., Beaudette, S., Wadji, D.L., Abou Chabake, S., Gonzalez, C., Jenkins, D., Kaptan, S.K., Lambert, J., Mossie, T.B., Spencer, R. (2024). Sex and Gender Considerations in Cross-Cultural Traumatic Stress Studies. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 15 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2024.2408194